Albert Camus in 1942 responded with a resoundingly blunt, ‘No.’ In literary form, he titled his answer The Myth of Sisyphus.

Confronted by the absurdity of life — our ever-seeking inclination toward hope and meaning and life set against the backdrop of disappointment and emptiness and death — Camus wrote, “There is only one serious philosophical question, and that is suicide.”

We constantly envision and then take on revisions of our lives: After high school, post-college, in the midst of our fourth tinkering session to get the ‘work-life balance’ scales just right as we hit our mid-life crises, and finally in the golden dusk of retirement. We come across situations that shatter our rose-colored glasses and make it difficult to carry on. And we begin to draw distinctions and categorize our worldview as we yearn for explanations to help answer why X, Y, Z happened when we were expecting A, B, C.

In the midst of all that making sense of the world, Camus reminds, “[t]hose categories that explain everything are enough to make a decent man laugh.” Though we use categories and labels and rationalization as a way to fill the gap between what we know and what we want to know, such posturing is emblematic of life’s absurdity.

And even in the midst of seemingly having made sense of the world as we know it, we must come to terms with the possibility that life may have been, crudely speaking, meaningless. Why, really, was it that two plus two equaled five? And five was then designated the time one gets off work like clockwork? And work was spread across terms like weekday and weekend? And…you see where I am going with this. (Likely nowhere?)

The more repetitive life becomes — and surely we all hit those points at their most acute one way or another, just think of that dreaded walk or drive to work on Mondays— the more consciously aware one becomes of life in its most absurd, meaningless, and unfiltered form. And the frustration that accompanies these realizations creates a glaring fork in the road: Simply put, you either commit suicide or you live with hope as your bedrock. Whether subconsciously or not, you choose one of these two paths.

Camus, though, doesn’t leave us hanging. He offers us a more authentic alternative.

His message: Life, despite being at times slowly peeled of rhyme and then suddenly stripped of reason, is not one unworthy of living. Despite being meaningless, life is worth living. Therein lies his life-affirming, fiery spirit: In the blatant presence of our own expiration date, we ought to rebel against mortality. Not with blind faith or hope, but with the painful yet real awareness of life’s meaningless tendencies. It’s this realization that sets us free.

How? Here’s the fun part.

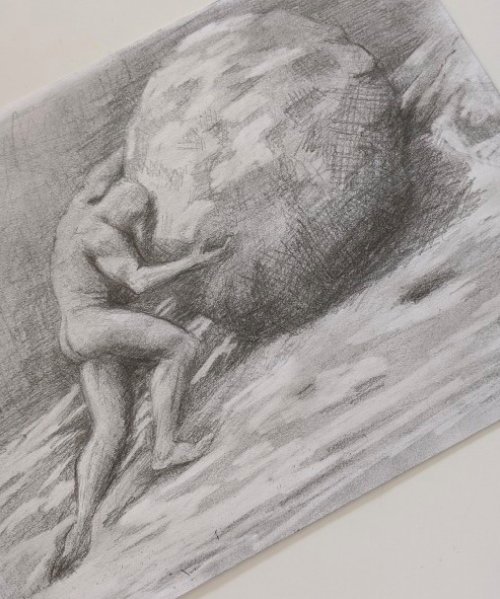

The mythology backdrop: Sisyphus, king of Corinth, twice escapes the narrow claws of death and manages to chain up none other than Death itself. As a karmic slap for such scornful treachery against the Greek gods, Zeus punishes him with futile labor and condemns him to ceaselessly push a boulder up a mountain only to then witness the boulder roll back down from its own weight. There is nothing he can do about it. Each time Sisyphus tackles the boulder anew, down the boulder goes again. On repeat. Eternally on repeat. And therein lies the tragedy: Sisyphus is conscious of his wretched condition.

Sound familiar? I bet. Sisyphus is human. It is important not to overlook this. Each time we are confronted by an endeavor that feels like it was ultimately for naught, we exhibit the same predicament as Sisyphus: A sigh of struggle. And— like my grandmother who so directly posed the following question over what would have been a pleasantly mindless cup of tea —each time we ask the question, ‘What is the point of living and having lived?’, we exhibit the same condition as Sisyphus: Consciousness.

Now, the philosophy portion: Despite the inherent helplessness, Camus calls on us to imagine Sisyphus happy. In fact, he implores us to do so when he writes,

“Each atom of that stone, each mineral flake of that night-filled mountain, in itself, forms a world. The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.”

Consider the boulder a culmination of X in your life — with X being your day to day; your life’s vision; your goals and experiences; or whatever else that defines you. When faced with dreadful realities in life — of which there are many — some of us cross our arms, make it known we consider life unbearably unfair and begin to wallow in our own self-perpetuating sense of victimization. Others, usually through the comfortable lens of group-think — add irrationality atop the inexplicable and turn to the religious community and this or that flavor of -ism. At an ironically skyrocketing rate, others, still, begin to adopt rebellious catchphrases concerning the disruption of the status quo. (See, e.g., a popular book titled Disrupt-Her: A Manifesto for the Modern Woman.) While most begin to look for external ways of coping with the absurdities of our lives, few consider it worthwhile to pause and look within.

Through Sisyphus, Camus invites us to learn to immerse ourselves in the human condition. To embrace it. Not to seek an answer to the absurdity of life, but to live through the questions, as Rilke says in one of his eloquently tender letters to a friend. Not to give up, but to stare at the monotony of life head-on. Perhaps dignify ourselves with an existential crisis or two after realizing the universe does not really look at us twice in the grand scheme of things. But to then return to home base, experiencing fully the life we are given rather than resenting it. In saying “hell yes” despite life’s suffering, Sisyphus chooses the noble path.

He chooses — day in and day out — to sort himself out and begin anew. He embraces all of life’s peculiarities and in so doing, affirms life over inevitable mortality. That is where, Camus suggests, happiness resides.

Rebel by sucking the marrow out of life in the most life-affirming acts you can think of. Swap Netflix for a chance to see the sunset over your neighborhood; say more than a passing hello to a stranger; ‘I love you’ is better said before it’s too late; don’t fall prey to half-baked ideas and trends and other people’s metrics of success; be rich in spirit and bold in your pursuits.

Why?

This quiet, internal revolution is the spark that will light up the greater flame. For a long time, I considered Camus’ Sisyphus very prone to complacency and a sucker for the status quo. Why doesn’t he just STOP rolling that damn boulder up? Why does he resign to breaking his own spirit with every step up the mountain? How do you get progress if you just swallow such punishment? But then, a thought: Perhaps we must first learn to welcome the gentle indifference of the world, as Mersault in The Stranger did before we go on changing it. And perhaps in exposing ourselves to the things that give us life and prompt butterflies in our stomachs in the midst of wretchedness, we learn to first sit with our values and principles without skipping steps and hurrying off to find any organization, cause, or movement to belong to for the sake of it. Finding something to cling to is easy. To actually have thought things through is the trickier part. It requires you to come to terms with you you are; to dare look in the mirror, and to choose the version of yourself that is it’s most authentic. Having lived through such a quiet rebellion, we find ourselves well-equipped in the big league.

Onward.